Can Seattle’s office market adapt and survive? It has before.

By Marc Stiles

It’s been over three and a half years since the pandemic shrouded the commercial office market in thick clouds of uncertainty.

Finally, the fog is lifting, but heavy pockets remain, particularly around remote and hybrid work, which has allowed tenants to reduce their footprints and rental costs.

Will the office market ever bounce back to pre-pandemic levels?

“The short answer on this is, no. We are at the new normal on office property and it’s been flat since December 2022,” Stanford University economics professor Nick Bloom said in an email to the Business Journal.

Bloom, who has researched remote work for nearly 20 years, said work-from-home days and building entry card swipe data “is not changing anytime soon.”

But the market will eventually come back, a recent survey of U.S. CEOs shows.

As reported recently by the San Francisco Business Times, almost two-thirds of the CEOs surveyed by accounting firm KPMG said they envisioned corporate employees will be back in offices within the next three years.

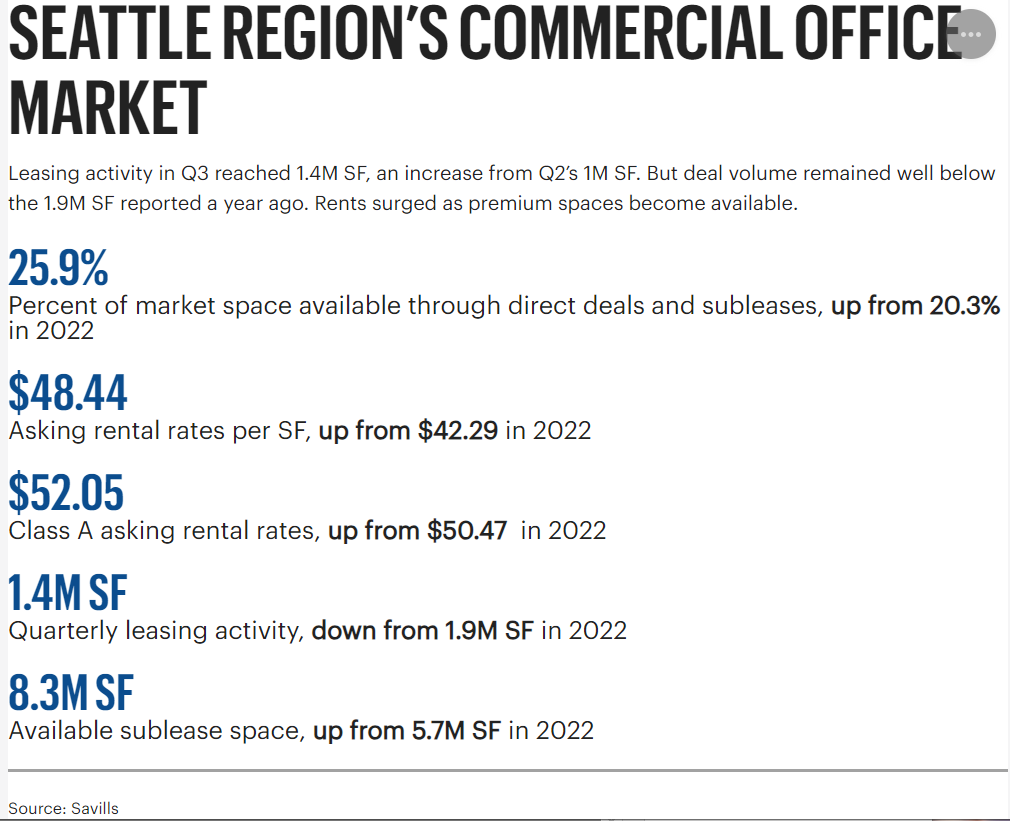

This downturn looks particularly bleak, with the overall availability rate in the Puget Sound region climbing to nearly 26% in the third quarter, 560 basis points over the same quarter last year, according to Savills.

But how bad is it, really?

It depends on one’s perspective, says Seattle developer Matt Griffin, who’s transitioning out of his longtime role at Pine Street Group to focus on investing and philanthropy. His career has spanned three downturns, including the one that began during the skyscraper building boom in the 1980s.

“We were way overbuilt,” said Griffin, who at the time worked at Wright Runstad & Co.

During this period, Wright Runstad developed the 1.1-million-square-foot 1201 Third Avenue Tower in Seattle, which formerly was called Washington Mutual Tower.

“We had to make a deal at 1201 at a loss to WaMu and buy their block at an inflated price,” Griffin said.

A decade later came the dot-com bust and then the Great Recession, caused by the bursting of the housing bubble, which in turn brought down WaMu.

It was not only the largest failure of an insured depository institution in the history of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., WaMu was also Seattle’s largest occupier of office space.

While tenants today can, and are, decreasing the size of their offices, the previous downturns were arguably gloomier.

“In the dot-com bust, you didn’t see companies shrink but go out of business,” said Griffin. Same with WaMu. “They just went away.”

Despite today’s sky-high office availability rate, Griffin is optimistic. In fact, he said he is “more than optimistic” due to the brainpower found in cities in general and the Seattle region in particular.

Boeing has been joined by Microsoft, Amazon and other tech companies as well as the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, the Children’s Research Institute and University of Washington Medicine, which ranks among the top academic research institutions to receive National Institutes of Health funding.

“While we’ve got some shrinking going on, I also think we’re going to see a bunch of new companies,” said Griffin. “We’ll get there.”

For that to happen, real estate developers will have to gamble on companies with no balance sheets. These nascent companies could blossom and grow to become sequoia sized.

Griffin was witness to this in the 1980s when Wright Runstad was selected to develop Microsoft’s Redmond headquarters.

“We talked about whether Microsoft had the credit or not for us to build their headquarters,” he said. “Look how stupid that turned out to be.”

In downturns over the last 100 years, it took five to 10 years for communities to reinvent themselves. Griffin said that’s not very long in the greater scheme of time. But when you’re in the middle of it, it can seem like forever.

Griffin says this rebound also will take a while.

To help spur things along, developers, owners and investors must be realistic about the current values of assets.

“That was part of what we at Wright Runstad had to do at 1201 Third. It forced us to go make a deal with WaMu at a loss we could tolerate,” said Griffin, an avid bicyclist.

He compared the market’s slog to pedaling up a steep hill you’ve previously conquered. Griffin says in the midst of it, you’re cussing because you hadn’t remembered how hard it was.

But when it’s over, you look back and say, that didn’t seem so bad.

Originally posted on the Puget Sound Business Journal. https://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/news/2023/10/16/office-market-matt-griffin.html